Beer vs. The Law

How Governments Quietly Control What Ends Up in Your Glass

Beer is one of humanity’s oldest “legal highs,” and that’s exactly why governments have spent centuries trying to control it.

Sometimes the law targets harm (health, violence, drink-driving). Sometimes it targets behaviour (where and when people drink). Sometimes it targets economics (tax revenue, protecting local producers, controlling imports). And sometimes it targets culture and religion.

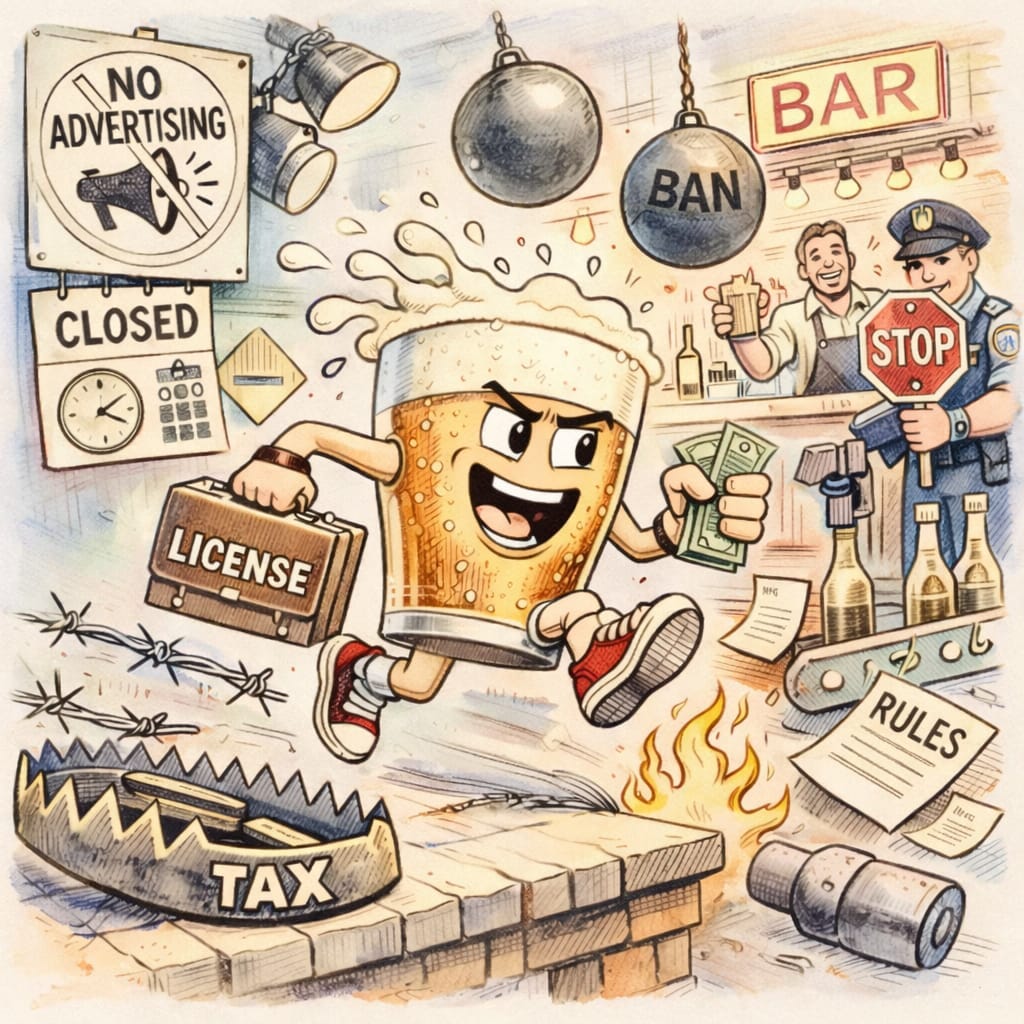

What’s fascinating is that “penalising beer” rarely looks like a single ban. More often, it’s death by a thousand paper cuts: restricted hours, restricted places, restricted advertising, restricted distribution, and pricing rules that quietly reshape what ends up in your glass.

Here’s a global tour of how beer gets boxed in and what it means if you’re a drinker, a brewer, or someone trying to build a brand internationally.

1) Total prohibition: when beer is simply illegal

In some countries, beer isn’t “regulated.” It’s forbidden.

Saudi Arabia has a long-standing alcohol ban, with punishments that can include imprisonment, fines, and corporal punishment; there are narrow exceptions (e.g., limited diplomatic access in recent years), but for the general public the prohibition framework remains.

Iran prohibits alcohol for Muslim citizens under the Islamic Republic’s legal framework. Beyond the obvious black-market issues, prohibition also creates a dangerous reality: unregulated alcohol and methanol poisoning incidents are a recurring risk.

What this “penalises,” in practice is not just consumption, but the entire ecosystem: production, imports, hospitality, and tourism patterns. It also pushes drinking (where it exists) into private or underground spaces, where safety and quality controls disappear.

2) Partial prohibition: “dry” states and regions inside otherwise “wet” countries

A country can be globally famous for drinking culture and still have regions where beer is treated like contraband.

In India, several states operate under prohibition regimes (commonly cited examples include Gujarat and Bihar). The result is a patchwork where crossing a state border can change the legal reality of beer overnight.

What this penalises is the movement, distribution, and brand-building. For brewers and importers, “India” isn’t one route-to-market it’s many different legal worlds.

3) State monopolies: beer is legal, but access is designed to be inconvenient

Some governments don’t ban beer they control it so tightly that “friction” becomes part of the policy.

In Sweden, Systembolaget is the retail monopoly for alcoholic beverages above a low ABV threshold (commonly referenced around 3.5% ABV). The intent is public health: reduce impulse buying, limit promotional tactics, and enforce age controls more strictly.

In Norway, Vinmonopolet plays a similar role, with the monopoly typically applying to beverages above about 4.7–4.75% ABV.

What this penalises is spontaneity and price competition. If you’re a brewer, it also shapes packaging strategy (ABV targets matter) and forces you into a specific listing/purchasing system rather than normal retail hustle.

4) Price-floor laws: beer is legal, but cheap beer becomes illegal

Some laws don’t say “don’t drink.” They say “you may drink but you can’t drink that cheaply.”

In Scotland, Minimum Unit Pricing (MUP) sets a legal floor price per unit of alcohol, and it was raised from 50p to 65p per unit in September 2024. That directly lifts the minimum price of high-strength, low-cost alcohol including certain beers and lagers.

The UK as a whole has debated similar mechanisms, and while England hasn’t fully adopted MUP, tax and duty still play a similar role.

What this penalises is the “value end” of the market. The cheap multipack, the strong white-cider equivalent, the high-ABV budget can. Craft beer often isn’t priced near the floor anyway, but the law still changes consumer behaviour and retailer promo tactics.

5) Tax as a behavioural weapon: beer is legal, but the government prices it upward

Most drinkers think of alcohol tax as revenue. In reality, it’s also policy: a way to steer consumption by making alcohol more expensive.

The UK operates a complex duty system based on ABV, with relief for small breweries.

France taxes beer more lightly than spirits, but still uses excise to shape consumption. Historically, wine has enjoyed cultural protection, while beer has been more tightly taxed and regulated.

Luxembourg is a fascinating case: Low excise duties and proximity to Belgium, France, and Germany have turned the country into a cross-border alcohol hub. “Fuel and beer tourism” is a real thing. Imported beer consumption in Luxembourg is around 63% of the total beer market compared to 15% in the UK.

What this penalises is small producers with tight margins, and price-sensitive consumers. It also quietly nudges the market toward lower-ABV products, smaller serves, or “nolo” options depending on how the tax regime is structured.

6) Time and place restrictions: beer is legal, but the clock becomes a cop

Some countries “allow” beer while aggressively restricting when it can be bought or consumed.

Thailand has long used time-based sales restrictions (famously an afternoon restriction historically associated with 2pm–5pm in many retail settings), and recent rule changes have drawn attention to how strongly drinking windows can be policed and revised.

Singapore restricts public drinking broadly: public consumption is not allowed in all public places from 10:30pm to 7:00am, under the Liquor Control framework introduced in 2015.

In the UK, licensing laws determine opening hours. Pubs, off-licences, festivals, all operate under tightly controlled permits.

France also regulates public consumption, especially in urban areas, where local bans can apply.

What this penalises is the nightlife patterns, convenience purchases, and “grab a beer and walk” culture. It also changes the business model: bars and hotels become the legal “funnels,” while casual off-trade becomes tightly managed.

7) Advertising bans: beer is legal, but you’re not allowed to talk about it

This is one of the most punishing categories for brands.

Lithuania introduced a comprehensive alcohol advertising ban effective January 2018, covering broad media including digital and is now widely cited as among the strictest marketing environments in the EU.

In France, the famous Loi Évin strictly limits alcohol advertising: no lifestyle imagery, no emotional storytelling, no glamour.

What this penalises: brand-building. When you can’t advertise, you’re forced into softer routes: point-of-sale compliance, on-trade relationships, experiential tasting (where permitted), packaging design, and organic word-of-mouth.

8) Distribution law: beer is legal, but the route-to-market is legally “walled off”

Some countries penalise beer not through consumption rules, but through how beer gets to the consumer.

In the United States, the post-prohibition three-tier system separates producers, distributors, and retailers (with variations by state). This structure affects everything: margins, speed to market, tap placements, self-distribution rights, and how small brands scale.

China is also a great example while beer is fully legal, distribution is tightly controlled through licensing, regional protectionism, and preferred local partners. For many foreign brewers, access to bars and retailers depends less on demand and more on navigating administrative and political gatekeepers.

What this penalises is the direct-to-consumer simplicity. For brewers, it often means slower expansion and heavier dependence on distribution partners and in many places, legal constraints make it hard to behave like a modern “consumer brand.”

The big idea: beer laws don’t just control drinking they shape beer itself

When you look across these systems, a pattern emerges:

Availability laws (bans, monopolies, hours) shape access.

Pricing laws (tax, MUP) shape who drinks what and how much.

Marketing laws shape which brands survive and how they grow.

Distribution laws shape who captures margin and who controls shelf space.

In other words: legislation doesn’t just punish beer. It redesigns the entire beer market.